Our meetings (that is our 'services') despite a reformation and the passing of centuries of social changes, remain modelled on a quasi pagan ritual: the Mass.

Maybe that has some references to the early church meetings, but I wonder.

Time to meet as Christians, not post-pagans; a fresh perspective:

At our church we have the opportunity to start fresh with a new 'service' in the middle of the day (at last, a concession to we night owls who regard 9am as early morning).

Start with morning tea, for about 15 minutes, then small conversation groups: even the smallest congregations could have three; five to seven would be the max. Then you need to spawn a new meeting. The max number of people in each group would be 7 (give or take), so once the group hits 35-49 people: spawn; or change format.

The small conversation groups could spring from a Bible verse, or some Christian experience, someone's latest reading, and might include prayer; maybe starting with prayer. These would be about 15 minutes.

Next we all come together for a talk: the 'sermon' de-liturgized. This might go for about 15 minutes. Any news could be given before the talk.

After the 15 minute talk we would return to small groups: same or different from before, for prayer.

After 15 minutes we'd come back together for a couple of songs, hymns, a short devotion (a couple of minutes) and benediction.

The whole thing could run from 45 minutes to 90 minutes, depending on people's choices.

Everyone would be encouraged to join the whole show, but would know that the talk would start at a fixed time, so they could just turn up for that. In fact, people could come and go for the segments of choice, to juggle other commitments they might have.

Congregations with a liturgical background might us liturgical forms for the segments: nice to stay in touch with our important traditions.

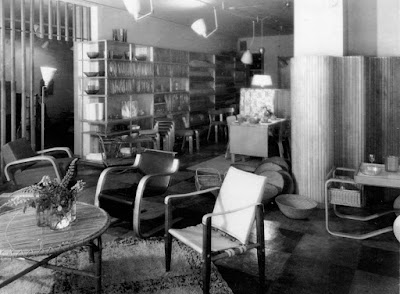

This should be held in an acoustically 'soft' space, at tables: that is not an echo-y hall, perhaps a carpeted space with drapery and an acoustic ceiling: it should be a well designed and attractive room that is warm and inviting: that lifts the spirit. So, there's a challenge for our architects.

Here's an image that might give some hints

Refreshments would be available afterwards: another cuppa, with food; lunch if some wanted to stay.

Serious teaching could be at another time, in seminar format:

pre-reading, or watch a short YouTube video, or listen to a podcast; a

more detailed talk, then discussion afterwards for about 20 minutes. The

whole thing should take an hour, ending with perhaps a song or hymn and

brief benediction.

An occasional Saturday afternoon intensive might be held three times a year to further knowledge and practice. This could be celebration as well as 'teaching'. Or we all just head up to Hillsong occasionally.

Sunday, April 30, 2017

Monday, April 10, 2017

Mindlessness

An article in The Sydney Morning Herald's The Good Weekend on Mindfulness triggered a follow up to my post on this topic.

A note I sent to one of our paid Christians on this topic:

A note I sent to one of our paid Christians on this topic:

Dear Filburt,

There was an article on 'mindfulness' in the Good Weekend on Saturday.

If you've not seen it, I've attached it, as I recall that you extolled

the virtues of this practice in a sermon some months ago.

I've been long acquainted with 'mindfulness' and related practices, and have pondered the nature of the approach to meditation that it represents.

As the article points out, the roots are in Buddhist practice. It therefore has to do with the Buddhist conception of the world. It follows, to my mind, that the preoccupation of mindfulness with the self in isolation has less to do with the world as the Bible portrays it: characterised in 'concrete reality', and more to do with the Eastern characterisation of reality as very much not concrete; rather, chimerical! Thus it harks to an dissolution of the individual in the amorphous depersonalised emptiness cooked up by Buddha and his demons.

I wonder, then, at the intended purpose of mindfulness in your reference to it and the positives of the practice that would displace (or even augment) God's provision in his word.

David enjoins us to mediate on the law; Yeshua to be in the personal presence of the Father in dependence upon him; Paul encourages us to pray without ceasing (for others).

These are entirely at odds with the solopsistic self-absorption of Buddhist/Zen/Hindu meditation, which seeks to produce a benefit by denying what is real, trapped in the ignorance of the Buddhist 'doctrine of creation' and its necessary flight from reality (contrast the Biblical doctrine of creation): that is, that we are persons in the image of God who is love (i.e., to be other-directed/in communion), called to fill our minds with his word.

There is a vast tradition of Christian 'mediation', which, as a writer in the Melbourne Anglican put it "The...focus...is an explicit form of prayer, not a conversation with the self, based on the conviction that salvation comes from God and not from ourselves. Christian mindfulness, by definition, is entry into the saving presence of the God, the holy Trinity".

Far better, I think, to teach and encourage spiritual engagement (as, for example in the long standing tradition of a 'quiet time') than a risky spiritual disengagement that could open the door to all sorts of trouble...as indicated by some of the research mentioned in the article.

I've been long acquainted with 'mindfulness' and related practices, and have pondered the nature of the approach to meditation that it represents.

As the article points out, the roots are in Buddhist practice. It therefore has to do with the Buddhist conception of the world. It follows, to my mind, that the preoccupation of mindfulness with the self in isolation has less to do with the world as the Bible portrays it: characterised in 'concrete reality', and more to do with the Eastern characterisation of reality as very much not concrete; rather, chimerical! Thus it harks to an dissolution of the individual in the amorphous depersonalised emptiness cooked up by Buddha and his demons.

I wonder, then, at the intended purpose of mindfulness in your reference to it and the positives of the practice that would displace (or even augment) God's provision in his word.

David enjoins us to mediate on the law; Yeshua to be in the personal presence of the Father in dependence upon him; Paul encourages us to pray without ceasing (for others).

These are entirely at odds with the solopsistic self-absorption of Buddhist/Zen/Hindu meditation, which seeks to produce a benefit by denying what is real, trapped in the ignorance of the Buddhist 'doctrine of creation' and its necessary flight from reality (contrast the Biblical doctrine of creation): that is, that we are persons in the image of God who is love (i.e., to be other-directed/in communion), called to fill our minds with his word.

There is a vast tradition of Christian 'mediation', which, as a writer in the Melbourne Anglican put it "The...focus...is an explicit form of prayer, not a conversation with the self, based on the conviction that salvation comes from God and not from ourselves. Christian mindfulness, by definition, is entry into the saving presence of the God, the holy Trinity".

Far better, I think, to teach and encourage spiritual engagement (as, for example in the long standing tradition of a 'quiet time') than a risky spiritual disengagement that could open the door to all sorts of trouble...as indicated by some of the research mentioned in the article.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)